Last week were engaged in our annual planning process. As part of this, we come up with key assumptions regarding the operating environment for the next three years or so. Interest rates, of course, are a huge variable in our business and dominated much of the discussion. Like most people, I suffer from recency bias whereby I’m heavily influenced by what has happened recently and find it hard to make predictions outside of that range. As a result, I thought that the 10-year Treasury would most likely be in a range of 1% to 3% during this time.

There was a discussion that there was a meaningful probability that we would experience a recession during this time frame. I was curious as to how low rates could go in the United States in the face of a recession and given the fact that rates have gone negative in Japan and the Euro Zone, particularly Germany, as the following chart shows.

I came across a policy brief from the Peterson Institute that attempted to quantify how low rates could go in the event of a recession based on the average effect of the 1990 and 2001 recessions. The model they used assumed that the federal funds rate would not drop below -0.50% and that in one approach the Fed did not use forward guidance to signal to the marketplace that rates would not exceed a certain level for a certain period of time and it would not engage in quantitative easing. The second model assumed the Fed uses both tools. Of course, these are just models and should be viewed with some skepticism. With that being said, it seems like the results make sense in that every recession since 1982 has brought lower rates than the previous one and I don’t see why this won’t be the case for the next one. I guess it also fits into my confirmation bias of believing that our variable rate strategy will benefit during a recession as I would expect Libor (or its replacement) to drop which would lower our cost of funds. This is, of course, beneficial to CWS and our investors. Conversely, Libor could rise which would increase our cost of funds and would be detrimental to our investors.

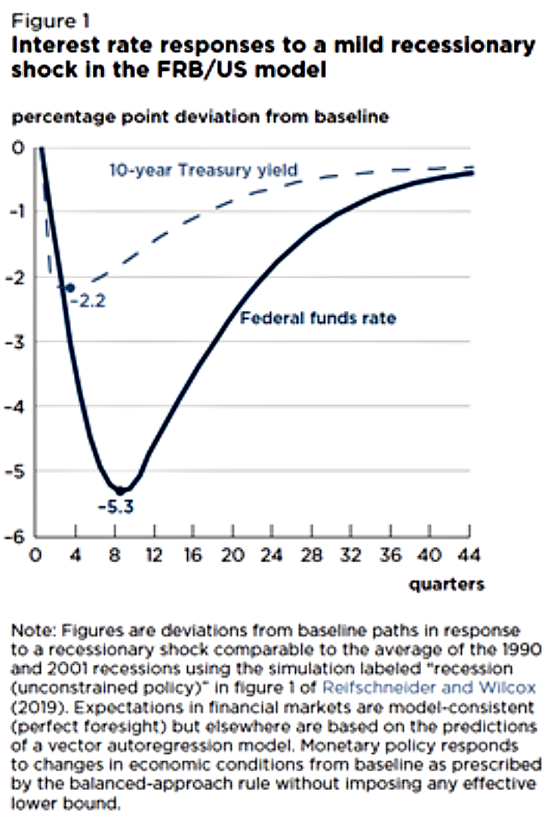

According to the authors, the following chart shows the impact of a recessionary shock on the federal funds rate (5.3%) and 10-year Treasury yield (2.2%).

From this analysis, the authors estimated that “any monetary policy action that reduces the 10-year yield 2.2 percentage points would have roughly the same effect on the economy as the cut in the funds’ rate shown in figure 1, whether short-term rates move or not. It follows that each 1 percentage point cut in the bond yield is equivalent to a 2.4 percentage point cut in the funds’ rate (because a 2.2 percentage point yield reduction is equivalent to a 5.3 percentage point funds rate cut).”

This next chart sort of falls into the category of “great minds think alike” as the authors assume that the 10-year yield, absent forward guidance, and quantitative easing, has a floor of 1%, which is what my gut told me would be the lower bound as well. When the other two tools are used, however, it shows it dropping to -0.30% while federal funds remain at its assumed floor of -0.50%.

Assuming that loan spreads don’t widen materially or index floors are implemented then this would obviously result in a much lower cost of funds to real estate borrowers.

To engineer 10-year yields down this low will require a lot of heavy lifting in terms of quantitative easing by the Fed. The authors cite research done by Federal Reserve economists that estimate that to move the 10-year yield lower by 1.3% would require total bond purchases of approximately $6.0 trillion. This compares to the $3.5 trillion expended between 2009 and 2014. The model assumes that yields drop by 2.0% so this would require a lot more Treasury purchases than $6.0 trillion.

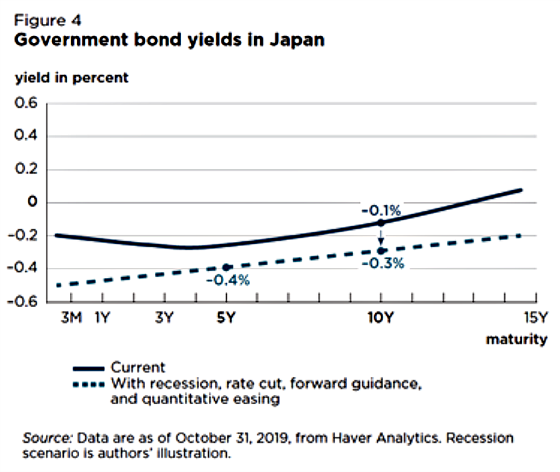

Japan has had short term rates lower than 1% since 1995 and has engaged in far more quantitative easing than the Federal Reserve based on a percentage of GDP. The following chart shows how little impact forward guidance and quantitative easing will be in Japan since rates have already come down so much.

The United States has much more policy space to take action in the event of another recession than the Euro Zone or Japan. If these models have any validity, then our cost of funds could drop by 1.5% to 2.0% if historical relationships between Libor and the federal funds rate hold. Our corresponding reduction in interest costs should then help provide us with some cushion in the event our Net Operating Income drops due to weakening demand due to recessionary conditions. Overall it appears that our heavy reliance on floating rate loans may be very beneficial to our investors if the authors’ modeling is accurate. Of course, these are simplified models and a number of variables outside of what is included here could impact rates both positively or negatively.

The analysis presented above is to illustrate the thought process and types of discussions we have internally at CWS. It is not intended to predict future performance or investor experience. Investment outcomes may vary considerably from our expectations.

Leave a Reply