In the famous opening and ending scenes of Dirty Harry, Clint Eastwood’s character asks the cornered criminal if he feels lucky. Does he think Harry Callahan’s 44 Magnum is out of bullets or does he think there is one left? Harry is going to pull the trigger regardless. This is a compelling metaphor of the markets and the Fed. The markets are essentially saying to the Fed go ahead and pull the trigger, we dare you. At best you have one bullet in your chamber if you are lucky but that’s all you have. Unlike in the movie, however, if the criminal is unlucky, the consequence is not death if the Fed raises rates against the will of the market. And just as the market suspected, the Fed held off in its September meeting. The next opportunity is December and we shall see what happens then.

Through all of the media chatter, Fed speeches, and never ending speculation of will they or won’t they, here has been growing consternation as to whether monetary policy has hit the wall in terms of its effectiveness with regard to generating more rapid economic growth and inflation.

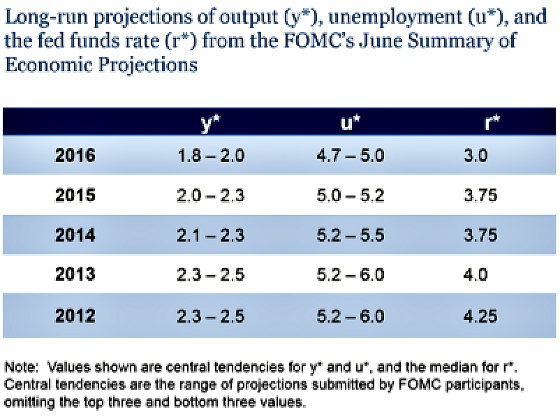

In a recent blog post writing from the catbird seats at the Brookings Institution, even Ben Bernanke lamented the poor forecasting record of the Fed. The following table from his blog shows how the Fed has consistently marked down its growth projections for GDP and the federal funds rate.

One may look at the table and say there is not that big of a difference between growth at 2.4% per year and 1.9% but, as Bernanke points out, on a cumulative basis it is quite significant. Bernanke writes:

“Relative to the underlying variables, these are large changes: For example, over a ten-year period, a potential growth rate of 2.4 percent (the middle of the 2012 range) cumulates to about a 27 percent total gain in output, whereas at 1.9 percent (the 2016 estimate) cumulative growth in ten years is instead about 21 percent, equivalent to a difference of about $1.1 trillion in GDP (in 2016 dollars).”

So why has the Fed been so far off?

I am an occasional follower of the work done by the Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI). Its focus has been on developing proprietary tools and indicators to help investors and economists understand where we are in terms of what inning we are in with regard to the business cycle and where we are headed. They have had a good track record of forecasting recessions and recoveries. In June 2016 they came out with an interesting report highlighting why the Fed has been off the mark and why it is facing enormous headwinds in terms of meeting its objectives.

ECRI’s research has led it to conclude that, with the exception of the first year of economic recovery, each recovery generates slower growth than the previous one. Economic growth is essentially a function of two inputs: labor utilization and productivity. The former is a function of hours worked which is a function of the size of the labor force, how many are employed, and how many hours each person works on average. This is largely a function of demographics which are quite well known and predictable. Productivity is more difficult to measure and forecast but from the table below it is clear that the labor composition’s contribution towards economic output has been relatively minor and that the real culprit has been falling productivity and capital intensity.

I have written recently about the aging of the world and how this should result in slower growth and keep interest rates low for a very long time. The ECRI report complements this demographic iceberg with significant challenges on the productivity front such that they believe that we have structural headwinds that monetary policy cannot overcome. The ECRI authors believe that our economy’s potential growth rate is only 1% per year on an inflation-adjusted basis. This is comprised of 0.5% for labor participation and 0.5% for productivity (multifactor productivity and capital intensity combined). The former is essentially baked in the cake while the latter is a result of a structural slowdown that has been taking place, particularly with regard to capital intensity. I recommend reading the report as to why the ECRI believes that, despite all of the technological changes taking place, it is not translating meaningfully to a more productive labor force.

The ECRI believes that the Fed’s aggressive monetary policy is the principal culprit for creating vast disincentives for businesses to spend and invest. By the Fed having its foot on the monetary gas in the belief that it was fighting cyclical trends, namely the sluggish growth that took place after the first year of recovery in 2010, versus structural ones, which the ECRI believes was a continuation of a long-term trend, the Fed has pulled demand forward by stimulating economic activity via more borrowing by corporations and wealthy individuals, along with driving asset values higher in a search for yield. Unfortunately, the issues were structural, ones that will be with us for the foreseeable future, and once the marginal value of leveraging up has maxed out, then the Fed will be faced with a large disincentive for businesses and individuals to spend as they seek to pay down debt and build up liquidity.

The authors argue that businesses that would not have been competitive in a higher interest rate environment have been kept alive by lower rates, thereby exacerbating the tendency for having too much capacity in the economy which creates deflationary risks and makes it far less profitable for businesses to invest and add capacity. This situation is made even worse by the incredible overinvestment by China in its productive capacity for commodities like steel and concrete and the inevitable slow down it is now contending with, and will for many years to come, due to its own demographic factors and as a consequence of such overinvestment coming home to roost. Unfortunately for those looking for the world to come out of its slow growth morass, we shouldn’t look to China as its leaders are reluctant to make the hard choices to restructure its bloated state industries for fear of the social unrest that may result. This will keep zombie companies alive and maintain overcapacity which puts downward pressure on prices.

In essence, according to ECRI, the Fed was using aggressive monetary policy to fight what they thought could be a secular deflationary threat, whereas the ECRI believed that it was cyclical and represented the natural tendency of the economy to grow more slowly after the first year of recovery in each subsequent expansion. The paradoxical impact is that it may have created some structural deflation as it has led to much more capacity and subdued profitability which will feed on itself as the Fed is forced to keep interest rates low for the foreseeable future. And when China is thrown into the mix along with a very slow-growing Europe and Japan who are embarking upon even more aggressive monetary experiments, the situation is compounded.

To put the structural slowdown in perspective, the authors assert that the first year recovery that took place between 2009 and 2010 of approximately 3% would have been the equivalent of 14% in the late 1940s!

This interesting report by the ECRI, along with some growing awareness by economists and even Fed Governors themselves (Brainard, Bullard, and Williams) that maybe monetary policy cannot cure all ills and that we are in a new regime in which the Philips Curve is not behaving like it did in cycles past, that demographics are a real impediment to faster growth, and that the slowdown in productivity may be with us for years to come (clearly the most debatable and contentious of the ECRI’s thesis). And yet, despite all of the evidence to the contrary, this is still this visceral need among some of the Fed Governors to “normalize rates” despite us being in a new normal of much slower trend growth. The March of Folly all over again in which ideology can lead to a self-defeating path with disastrous outcomes. While I don’t think it will be disastrous because markets will brutally punish the Fed if it goes too far as evidenced by the reaction of global markets even with the hint of one interest rate hike. It seems to now take the Fed about a year to implement one hike as it telegraphs the potential for a hike, markets sell off, economic data comes out contradicting the Fed’s position, markets recover, the data improves, the Fed signals it is open to another rate, the markets ignore the Fed, data improves, the Fed becomes more serious, markets sell off, and the beat goes on.

My bias is in the slow growth camp and until proven otherwise I continue to believe that interest rates will stay low for the foreseeable future.

These are the last words of Inspector Harry Callahan and are quite applicable to the situation facing the Fed in the face of very skeptical markets:

“Being this is a 44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and would blow your head clean off. You’ve got to ask yourself one question. ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well do you punk?”

Well, do you Fed Governors?

Over to You:

Well? Does the Fed feel lucky?

Excellent piece. Given the many headwinds facing US and world economies, not the least of with are rooted in demographics, the burden of proof is squarely on those who think growth accelerates beyond the tepid “new normal”. Separately but loosely related, there is election talk of facilitating repatriation of corporate earnings stashed overseas. Should that occur, the advertised flood of new jobs is not likely to occur as many of the jobs that have disappeared are most certainly gone foresver. Repatriation would likely result primarily in debt reduction, share buybacks and dividend increases.